We are inching towards the historic seventieth Republic Day of India - 26th January 2020. It was on this very day - 26th January - in 1950, that post ‘our tryst with destiny’, we gave ourselves an extraordinary gift - the Constitution of India. While wishing all my fellow countrymen and friends a very happy 70th Republic Day in advance, I wish to take this momentous occasion to write about the beauty of our artistically elegant Indian Constitution, the only one of its kind with such an artistic elegance, which has served us very well for all of seven decades and will continue to do so for eons, notwithstanding our vastly diverse and quite complex nature of our country and its citizens. It is therefore no wonder that the Indian constitution not only continues to intrigue and impress people across the world but also inspires national and international constitutional experts.

The original Constitution is now safely and securely stored within a vault like room in the Library of the Parliament of India in New Delhi. It is housed inside a helium filled case which measures 30x21x9 inches in size. The storage maintains the exacting standards of the climate control, which are used in most museums. The temperature is maintained at 20° C (+/- 2°C) and the relative humidity is maintained at 30%(+/-5%), throughout the year. Inside this climate controlled nitrogen laden case lies our original Indian Constitution which is a 251 pages long manuscript. It weights around 3.75 Kgs.

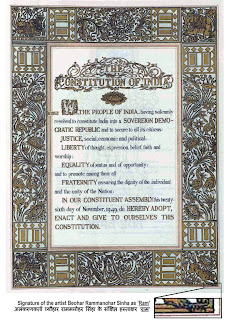

The Indian constitution with some 90,000 odd words, is the longest constitution of any sovereign nation in the world. The original constitution of India, which is stored in the library of the Parliament of India is made of 22 parts, 395 articles and eight schedules. The beauty of this original constitution is its aesthetics, which is sure to mesmerize anyone’s eyes. Each of the letters, quotation marks, parentheses and the numbers are all so perfectly hand written with artistic elegance of calligraphy and not one word is misspelled, and not one blotch of ink is seen any where. The perfection of the calligraphy and the italics are so immaculately penned that it is almost impossible to surmise that the constitution has actually been hand written by a man named Prem Behari Narain Raizada(Saxena). Our Constitution is the longest hand written Constitution of any country in the world.

It provides a comprehensive framework for guiding and governing our vast country with much greater diversity. Our constitution has been framed keeping in mind our social, cultural, religious, linguistic and innumerable other diversities, which are integral to India. The opening and last sentences of the preamble of our constitution - “ We, the people... adopt, enact and give to ourselves this Constitution” - signify that the power to govern our nation lies in the hands of we the people of this great country. The objectives specified in the preamble constitutes the basic structure of our Constitution, which cannot be amended and therefore we the people of this country will continue to be central to the governance of India.

The Constitution of the Republic of India was approved by the Constituent Assembly on November 26, 1949 and our Constitution came into effect two months later on 26th January, 1950. Ever since, this day is being celebrated all across the country as the Republic Day. The inaugural Republic day (26th Jan 1950) celebrations began in Delhi with the 34th and last Governor-General of British India, Chakravarti Rajagopalachari, reading out a proclamation announcing the birth of the Republic of India. The new President, Dr. Rajendra Prasad, was then sworn as the first President of India. Rajendra Prasad began his address to the nation by stating “today for the first time in our long and chequered history, we find the whole of this vast land ..... brought together under the jurisdiction of one constitution and one Union, which takes over the responsibility for the welfare of more than 320 million men and women.”

Although we achieved our independence from Britain on August 15, 1947, yet, for the first two years and few months thereafter, we continued to be largely governed by the colonial Government of India Act of 1935. However, shortly after independence was declared, the Indian constituent assembly - elected by the then provincial assemblies - took upon itself the responsibility of preparation of a constitution for us that would govern our new independent nation. The farmers of our constitution, headed by Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar, after elaborate research, consultation and discussions - that spanned more than two years - prepared a final draft of the constitution. This was approved by the constituent assembly on 26th November 1949, post a healthy discussion in the assembly. However, January 26 was chosen as the official constitution enactment date primarily because it was on this very day - January, 26, 1930 - that the Indian National Congress, who were spearheading the freedom movement for India, had announced Purna Swaraj (complete self-rule) and Declaration of Independence.

Subsequent to the adoption of our constitution, we officially came to be known as the Republic of India, a sovereign, socialist, secular, democratic republic that secures all its citizens; justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity, according to its preamble. The original text of our constitution was made up of 395 articles in 22 parts and eight schedules. The Indian constitution is not cast in die and continues to evolve and has been amended more than 100 times including some of the recent amendments. Our constitution is the mother of all other laws of the country and it is one reverence on which the four arms of our democracy - legislature, judiciary, executive and the media - swear. Every single law enacted by the Government has to be in conformity with our constitution.

The beauty of our constitution lies in the fact that the policy makers and the framers of Indian constitution took cognizance of the multivalent diversity of India and deliberated on a framework that would provide for a unified but culturally diverse nation-state. It is with this objective that the Indian constitution was framed and adopted. Our Constitution, though influenced by Euro-American constitutions, is absolutely Indian in its spirit and is embodied in the form of fundamental rights, directive principles of state policy and fundamental duties.

"We, the People of India” - the very phrase with which our constitution begins, signifies the very idea of India - unity in diversity. India is a land of diversities in every sense of the term. The phrase कोस-कोस पर बदले पानी, चार कोस पर वाणी…, symbolises the diversity of India in terms of language. Hundreds of languages are spoken across India, which have different dialects. India is also a country of divergent races, where one race is altogether different from the other in its language, culture, food habits etc. In terms of culture, heterogeneity reaches its climax. Indian state has different cultures within the same area and among the people of different castes, religious groups and tribal affiliations. Religion-wise, Indian state remains heterogeneous in the context of presence of different dominant religious groups within the country. Diversity within a religion reaches its climax among Hindus to the extent that so many scholars, including our Supreme Court, have said that - Hinduism is not a religion, but a common-wealth of the faiths that originated from the sub-continent. Keeping in view this diversity, the founding fathers of the Indian constitution made unity in diversity the bed- rock of its foundation.

Our constitution is not framed for any single community of persons but for all the citizens inhabiting this vast country, irrespective of caste, creed, race or religion, implying the notion of multiple identities belonging to different cultural markers. This feeling of oneness is further exemplified with the insertion of the words 'Fraternity', 'unity and integrity' involving a spirit of brotherhood and harmony amongst all the people. Our constitution makes it evident that the framers made a very judicious choice of words of brotherhood, particularly because during the period of framing of the Constitution, India was passing through a critical juncture of partition. The country had just been partitioned on the grounds of religion and the framers of the constitution had to be very cautious not to hurt the sentiments of any of the different religious communities. Since independence, the framers of our constitution knew it very well that unless and until the diverse entities are given proper constitutional recognition, India will not be able to preserve its hard-earned unity. Our constitution is central to the unprecedented success and glory of India. It has helped our ruling class to keep two things going at the same time- infinite variety and unity in that variety.

The Constitution of India stands out as a fascinating piece of art, which is written in both Hindi and English languages. It took almost 3 years to create this extraordinary piece of art. The calligraphy of this handwritten and handmade constitution book is credited to Prem Behari Narain Raizada, and the book is richly illustrated in miniature style drawings and paintings by one of the best artists of the time, Nandalal Bose and his students. It is signed by the framers of the constitution, most of whom are regarded as the founders of the Republic of India. The original copy of the Indian Constitution is preserved safely in a special helium filled case in the Parliament Museum, which incidentally was developed by Dr Saroj Ghose, the first Director General of NCSM - our council.

The founding fathers of our nation wished that the Constitution of India, should not just be a governing document, but it should also represent the rich heritage of India. Their vision became a reality and our constitution is the only Constitution in the world, which is handwritten and richly illustrated with drawings and motifs that have been inspired by the murals of the famous Ajanta caves & the miniature paintings. It is this artistic elegance and handwritten calligraphy that makes the Indian constitution stand out in comparison with others. When the Indian Constitution was being drafted, the members of Constituent Assembly thought it would be appropriate, if the document could somehow represent India’s historic journey and heritage. The Congress entrusted one of the leading artists of the country - Nandlal Bose - with the task of illustrating the pages of our constitution. Bose selected a team of artists from Shanti Niketan, who made 22 images for the manuscript of the Indian Constitution.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chairman of the Drafting Committee of the Constitution, is very well known as its architect, but unfortunately very little is known about the man who literally penned the Constitution nor the artists who richly illustrated this document. When the draft of the Constitution of India was ready to be printed, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru wanted it to be handwritten in a flowing italic style. He therefore approached the renowned calligrapher Prem Behari Raizada with the proposal of handwriting the entire Constitution in calligraphy.

Prem Behari, born in 1901, came from a family of traditional calligraphists and his grandfather, Ram Parshad Saxena, was a scholar in Persian and also a highly accomplished calligrapher. He taught Prem Behari calligraphy, which is an art of producing decorative handwriting or lettering with a pen or brush. When Pandit Nehru requested Raizada, to write the constitution, he accepted the honour but refused to accept any remuneration for his hard and patient work. In return for his labour of love, Behari Ji requested Pandit ji that he be allowed to write his name on every page of the Constitution and on the last page, he be permitted to write his name along with that of his grandfather’s name. Pandit ji agreed to his request and entrusted Prem Behari the prestigious yet an onerous task of writing the Indian Constitution in beautiful hand calligraphy. Prem Behari was allotted a room in the Constitution Hall - which later came to be known as Constitution Club - for writing the Indian Constitution. The original manuscript of the Constitution was written on parchment sheets measuring 16X22 inches, which will have a lifespan of a thousand years. The finished manuscript consisted of 251 pages and weighed 3.75 kg. Records reveal that in all, 432 pen holder nibs were used by Prem Behari for this calligraphy-writing of the entire Indian Constitution.

Since the members of the Constituent Assembly had envisaged that it would be appropriate if the Constitution could represent India’s journey and heritage in artistic styles, the Congress, who by then had seen the extraordinary work of art by Nandlal Bose, particularly those posters that he had designed for the congress meetings, entrusted the task of artistically illustrating the pages of the Constitution to depict the journey of India to Nandlal Bose. Nandlal Bose, gladly accepted this task as a nations calling and carefully selected a team of artists (Biswarup, Gouri, Jamuna, Perumal, Kripal Singh and other students of Kala Bhavana) who would help him depict a fragment of India’s vast historical and cultural heritage. Nandlal Bose and his team created chronological illustrations, which narrate the story of India, using indigenous techniques of applying gold-leaf and stone colours. They designed the borders of every page and adorned them with beautiful art pieces, in the miniature style. The “Preamble” page was done by Beohar Rammanohar Sinha. Nandlal and his team of artists created scenes from our national history. For example the Vedic period is represented by a scene of Gurukula, and the epic period by a visual of Ram, Sita and Lakshman returning home and another of Krishna propounding the Gita to Arjuna on the battlefield. There is a beautiful line drawing of Nataraja, as depicted in the Chola Bronze tradition. Then there are depictions of the lives of the Buddha and Mahavira, followed by scenes from the courts of Ashoka and Vikramaditya. Other great figures of our history who are represented include Emperors Akbar, Shivaji, Guru Gobind Singh. The Freedom Struggle is depicted by a series of heroes starting with Rani Lakshmibai, Tipu Sultan to Gandhi’s Dandi March. It also takes into account his tour of Noakhali as the great peacemaker. Subhash Chandra Bose also finds a place in one of the artwork, which has been dedicated to him in the Constitution. As can be seen in the Constitution, Nandlal Bose not only used narratives from ancient Vedas, Mahabharata and Ramayana but he also depicted the contributions of modern and contemporary freedom fighters that included tales of Mahatma Gandhi and Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose. The section on fundamental rights, which often comes during discussion, features a scene from Ramayana. Gandhi ji’s Dandi March is depicted in the section on official language. In part XIX, Subhash Chandra Bose is seen saluting the flag ; a painting of Tipu Sultan is seen in part XVI, King Ashoka the Great is seen propagating Buddhism in part VII, while ocean waves can be seen in part XXII.

The preamble page of our constitution was created by Beohar Rammanohar Sinha, a Jabalpur native who also studied art in Shantiniketan. Sinha extensively studied the art and aesthetics of Ajanta and Ellora Caves, Sanchi, Sarnath and Mahabalipuram and used traditional motifs such as Padma, Nandi, Airavata,Vyaghra, Ashwa, Hans and Mayur to pictorially convey the very essence of Indian Constitution.

Dr Rajendra Prasad, the first President of India became the first person to sign the Constitution of India on 24th January 1950 while Feroze Gandhi, who was then the President of the Constituent Assembly, was the last one to sign this constitution.

The Constitution of India, is like the Gita, Bible or Quran for governance of our country and it has a rich and artistically elegant wonderful story to tell of we the people of India. Although it is often stated that our constitution is framed from the borrowings from other countries but what it does not borrow from anyone in the world is it’s rich artistic heritage, which has been captured in this document by artist Nandalal Bose and his fellow artists.

During my tenure as the Director of NGMA, Mumbai I was privileged to see one of the copies of the Indian Constitution, which is also in the collections of Delhi and I also had the honour to see several works of Nandlal Bose which are also in the collections of NGMA Delhi.

Once again wishing you all a very happy 70th Republic Day in advance and I join all Indians from across the world in praying for our motherland.

Jai Hind.