Verghese Kurien: Remembering the “Milk Man of India” on his birth centenary

Images : Courtesy Amul, Wiki Commons and Nehru Science Centre.

It was on this day, 26th November, 1921, that Varghese Kurien, the milk man of India, who transformed the dairy movement in our country was born. He ushered in the white revolution by empowering small and marginal farmers and landless labourers to partake in the revolution that he brought about to make AMUL truly the taste of India and today, as the nation celebrates his birth centenary, I wish raise a toast in memory of Padma Vibhushan Verghese Kurien and pray for his memories and contributions to be ever etched in the hearts and minds of all Indians and in the annals of the Indian history. The reverence that the nation has for Kurien stems from the fact that his contributions impacted on the lives of millions of cooperative dairy farmers - including the marginal farmers - not just economically but also socially and politically. Dr. Kurien believed that where agriculture was concerned, the farmer was the most important part of the entire food cycle. Without the farmer there would be no role for the processor, market maker and the distributor. Hence, he should get the highest share of the market price of milk. The profundity of the belief that Dr. Kurien laid of the importance of farmers is now poignant in the current context of the famers protest.

The impact of the cooperative dairy movement in India and how it empowered our famers and brought out a paradigm shift in benefitting the famers, can serve as an example to other sectors is something which it is necessary for us to understand in the light of the current continuing farmer’s agitation. Even after the Honourable PM of India has announced the roll back of the three farm laws, the agitation seems nowhere near to getting completely resolved, thus creating more inconveniences to the people – farmers included. Today when we are seeing an unending debate and a cacophony of political noises made on the issue of farmer’s agitation and the demand for a legislation on MSP - all with a purported motive of benefiting our farmers -, it is pertinent to recall the contributions of Dr Verghese Kurien and how his path breaking dairy movement in India relied on the favourability of the liberalised markets on the growth of the dairy sector, rather than the government support and interventions. May be the success of agriculture segments like horticulture, dairy development, fisheries - which grew by an average 10% annually with little or no intervention of the government on the market - can help the stakeholders of the farmer’s agitation to convince the farmers to have a relook on their demands. It is also pertinent to note that during this very period when sectors like milk, horticulture and fisheries were growing at 10% annually with little or no intervention of the government, the growth rates in cereals and other agriculture produce for which MSP is being demanded, grew at just about 1%, which could be an outcome and uncertainty of the intervention by the government.

There are many essays written on the pros and cons of the farmer’s demand for the legislation on the MSP, and how, prime facie, it appears that the cons of the MSP can be quite detrimental to the very interests of the farmers in the long run. Therefore, today when we are celebrating the birth centenary of Dr Verghese Kurien, it may be pertinent to highlight the contributions of Dr Kurien in bringing about a revolutionary change in the lives of the people through his dairy moment and how this movement impacted the lives of the marginal farmers. The white revolution which the country witnessed was in fact, a by-product of the empowerment the Dr Kurien brought about through the Amul-model (also known as Anand-pattern) dairy cooperatives.

On the birth centenary of Dr Verghese Kurien it is an honour for me to be sharing my tribute to the legendary nation builder who touched the lives of millions of people by empowering them. I am tempted to open my tribute to Kurien by recalling that extraordinary moment when I had the honour to meet Dr Kurien in person at his karma bhumi – Anand – sometime during April 2003. I was accompanied by my colleague Nitin Pradhan, from the Nehru Science Centre, for an important task of conducting an interview with the milk man, Dr Verghese Kurien for use in the National Agriculture Science Museum (NASM) a project which our parent body NCSM was assigned for completion on turnkey basis at New Delhi, inside the ICAR campus. I was then working as the Curator and head of Electronics and Computer section at the Nehru Science Centre, Mumbai.

I vividly remember that I had written a request letter to Dr Verghese Kurien and addressed it to him as the Chairman of Institute of Rural Management, Anand, and asked for an appointment for the said interview. His Secretary, one Mr Jacob Fernandes (I hope I got his name right) wrote back to me asking for more details before he could try and fix an appointment. I spoke to Mr Jacob and briefed him about our requirement and he somehow became quite friendly with me. Mr Jacob also helped me to speak to Dr Kurien over phone and I had the honour to brief him of the NASM project and our requirement of his interview in the Dairy section of the museum. He was so very kind to inform me that although he is normally averse to such interviews, considering the cause he agreed to give me an interview and asked me to coordinate with Mr Jacob. By then I became friends with Jacob, who gave me lot of background information and also narrated about an incident when Dr Kurien got so very angry with a journalist who had come completely unprepared to interview him. He cautioned me to come well prepared for the interview. I requested Mr Jacob if he could also arrange for a visit to the milk collection centres and for an interaction with some of the small and marginal farmers who are contributing at the milk collection centre, which he did.

My colleague Mr Nitin Pradhan and I visited Anand and we were accommodated at the IRMA guest house and were pleasantly treated as the guests of Dr Kurien, courtesy Mr Jacob. We had a full day visit to the milk collection centres, which we witnessed at around 5 in the morning, where we could meet the foot soldiers of this massive milk revolution and record their impressions. We also visited many other facilities of NDDB and had an opportunity to interact with some of the very senior officers at all the places courtesy Mr Jacob who had briefed them all that it was at the instance of Dr Kurien that we are visiting these facilities. I can never forget this visit, which gave me an idea of what a profound transformation that Dr Kurien brought about at Anand, the place from where his tryst with Indian dairy movement began. We also had the honour of visiting some historical places in the NDDB campus including the small room where the young Verghese Kurien stayed when he first arrived at Anand. With inputs from Mr Jacob and so also my own research I was fairly well prepared for the interview with Dr Kurien. Yet, my tension and apprehension was palpable, more so since Dr Verghese Kurien had walked out of an interview with one of the journalists who had come to interview him few months before.

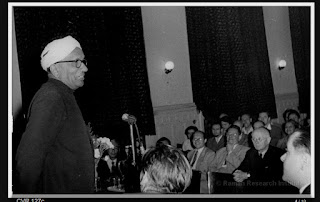

The momentous occasion came and my colleague Mr Pradhan and I had set up the camera and made all arrangements for the interview and we were waiting for Dr Kurien to arrive. We got up in reverence when Dr Kurien entered and we exchanged greetings with him. He asked me to brief him about the NASM before conducting the interview and I was very well prepared on this and I explained in great details the importance of the Agriculture Science Museum, which we were tasked to develop on turnkey basis at the Pusa campus of the ICAR. He seemed quite satisfied with the background information that I gave to him. It was now the time for action and we had an excellent freewheeling interview, which though scheduled for just 20 minutes went on for more than an hour and he appeared to be impressed with the ground work and research that we had done for this interview. Even after the interview he spent some more time with us including narrating some of those nostalgic memories including of his initial reluctance to be at Anand, a place where the culture of the city was completely in divergence with the place where he had grown up and how this very town become integral to him. Although he was aged 85, yet, his memory was very sharp and so was his intellect and also the vision that he continues to hold for the nation. Soon after the interview he called his PS, Mr Jacob, and asked him to arrange for our visit to the high mast musical clock tower, a unique feature which was commissioned at the IRMA campus at his instance, which we had the honour to experience. When we left the campus for our return journey, the visit and our interaction with Dr Kurien had left a lasting impression on us that even today while I am penning this tribute, those moments are crossing my mind so vivaciously. When I spoke to my colleague Pradhan about our visit to Anand this morning, I had a pleasant surprise waiting. He not only recalled the visit he also informed me that he will try and search a copy of the interview and therefore asked me to wait before posting this on the Blog. By this evening he had searched his archive and found the interview. Seeing the interview those memories of our interaction with Dr Kurien have become so very fresh and has made me quite nostalgic and I am including couple of images drawn from the video interview in this blog.

Dr Kurien was born on November 26, 1921 at Kozhikode (Calicut) in the district headquarter of Malabar, which was then the part of the Madras Presidency. His father Puthen Parakkal Kurien, was a Civil Surgeon and a well-to-do doctor. Kurien had a blessed ambience at home and he had good schooling and graduated in Science from the Loyola College in 1940. He subsequently enrolled for subject of his passion – Engineering - and obtained his engineering degree in Engineering from the Guindy College of Engineering in Chennai. This was a time when India was passing through freedom struggle and the world was witnessing the dreaded WWII. There were limited opportunities and among them one of the best was TISCO. Kurien joined the TISCO Technical Institute as a graduate apprentice in 1943 and after his training at the institute he started his career as an Office Apprentice in TISCO. The end of the WWII was a period when the British had decided to award nearly 1000 scholarships to bright graduates to be trained in the best of institutions in England and US and among those who were its beneficiary was Dr Kurien. Prof Satish Dhawan, whose birth centenary was celebrated last year was another beneficiary of this government scholarship and rest is history and he ended up as one of the key architects who helped transform the vision of the father of Indian Space Program – Dr Vikram Sarabhai in to reality. Dr Kurien was one of the beneficiary of this prestigious Indian scholarship. By then Kurien had spent two years at TISCO and had realised the importance of technology. He left TISCO when he obtained the Govt. of India’s scholarship to study Dairy Engineering. Unfortunately, he was more interested in studying mechanical engineering, however he was happy to take what he got, since this was a prestigious scholarship that could shape his future. Before taking up his studies in dairy engineering in US, Kurien decided to undergo some specialized training at the Imperial Institute of Animal Husbandry & Dairying, Bangalore for getting acquainted with this new subject. Fortunately for Kurien, the college that he was awarded for his studies did not have a specialized dairy engineering department in the US. He left for the United States to take up his scholarship from where he completed his Master’s degree in Mechanical Engineering with Dairy Engineering as a minor subject from the Michigan State University in 1948. He was quite happy that he had an opportunity to study the mechanical engineering subject which he relished. The government scholarship which Kurien and many others got had a clause for the recipients. They were expected to execute a bond with the government to serve the government at the place of their posting for at least a minimum of 6 months. Accordingly, Dr Kurien was asked to join the Government Creamery to serve his bond with the government on his return from US. This was located at Anand in Gujarat. It was this assignment, which he assumed reluctantly, that turned out to be his tryst with his dairy movement and with the city for the rest of his life.

Kurien arrived at Anand on Friday, the 13th May 1949 and all he had in his mind when he landed at Anand was to serve his bond period and move out of Anand for a greener pasture post his mandated bond period at Anand. By the time he ended his bond period working with the Government Creamery and he received his relieving order and as he was getting ready to move to Bombay (now Mumbai), as destiny would have it, he came in contact with his future guru and mentor, Shri Tribhuvandas Patel, the then Chairman of Kaira District Co-operative Milk Producers Union (KDCMPUL), which later went on to become the house hold name across India Amul. Incidentally the sudden growth in the Anand model of cooperative was the reason for finding a new name to KDCMPUL. When Tribhuvandas and his compatriots were contemplating on a new name for their dairy, the word ‘Amul’ was suggested by a chemist, around 1957. The roots of this word came from a Sanskrit word “Amoolya”, which means priceless. Fortuitously this word also stood as an acronym for Anand Milk Union Limited.

Tribhuvandas Patel was a freedom fighter and also an associate of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. He managed to convince Kurien to stay on in Anand for some more time and help him in commissioning some of the equipment which he had ordered for Amul. Tribhuvandas had bought new machinery, which were aimed at increasing the capacity of the cooperative from 200 litres of milk in 1948 to around 20,000 litres in 1952. The offer sounded quite interesting to young Kurien, who had immense interests in machineries. Therefore, Kurien decided to stay back for a few more days until commissioning of the new equipment for the cooperative. Kurien was under the impression that he was staying back to help Tribhuvandas with whom he had befriended. But then his involvement of commissioning the equipment at the dairy exposed him to the social service of Tribhuvandas and how his vision was aimed at empowering the poor and marginalised farmers. The more Kurien got to know Tribhuvandas and his social works, the more interest he started taking in his works and he slowly started imbibing the spirit behind the dairy and the co-operative society that his Guru Tribhuvandas Patel had started. As fate would have it, those few extra weeks that Kurien had decided to spend at Anand for the commissioning of the dairy equipment turned out to be the most crucial period in his life, which motivated him on to stay at Anand forever and the rest that happened is now history.

The Kaira District Cooperative Milk Producers’ Union Limited (KDCMPUL), which soon came to be popularly known as Amul Dairy, was formed in 1946. It heralded a new dawn for the marginalised farmers who were exploited by the Britishers who controlled milk production by Polson. Kurien, Tribhuvandas Patel and Kurien’s friend and dairy expert HM Dalaya changed all that. Dalaya, invented a method of making milk powder and condensed milk from buffalo milk. This new concept revolutionised the Indian dairy industry, since until that point such processed items could be made only using cow’s milk. This success of the Amul Dairy was soon replicated in many of its neighbouring districts of Gujarat. The ground breaking works of Kurien, Tribhuvandas and Dalaya prompted the then Prime Minister, Lal Bahadur Shastri ji to establish the National Dairy Development Board (NDDB). NDDB was established in 1965 to replicate the cooperative movement of Amul and expand it across India.

Kurien from mantling the role of an engineer at AMUL was groomed into a General Manager of the company and Kurien immersed himself in fighting for the cause of poor farmers. He occupied various positions in his career in Anand, starting from Executive Head of Kaira Union in 1950, to becoming the Founder Chairman of National Dairy Development Board from 1965 to 1998, the Gujarat Co-operative Milk Marketing Federation Ltd, from 1973 to 2006. Dr Kurien, in the year 1979, established a dedicated institute “Institute of Rural Management” in Anand (IRMA), which was primarily aimed at grooming professional managers for the management of the cooperatives. He served as the Chairman of IRMA from 1979 to 2006. It was at the office of the Chairman IRMA that we conducted the interview of Dr Kurien. Dr Kurien dedicated his entire professional life in empowering Indian farmers through co-operatives. Dr Kurien, in the year 2006, quit the position of the chairman of the Gujarat Cooperative Milk Marketing Federation (GCMMF) following dwindling support from new members on the governing board and mounting dissent from some of his own protégés, who had termed his working style as being dictatorial. Some of these moves, however, were backed by political forces that sought to make inroads into district unions of the cooperative dairy.

By the time he quit the position of the Chairman of GCMMF, Dr Kurien had laid an extraordinary and a robust foundation for developing a democratic enterprise at the grass roots and had translated his profound vision of ensuring economic empowerment of the people involving the very people in this movement, in to a reality. An engineer at heart Kurien believed that by placing technology and professional management in the hands of the farmers, the standard of living of millions of our poor people can be improved and the results are there for the world to see and acknowledge.

For his extraordinary contribution to the cooperative movement and for the empowerment of the people and so also the success of Amul and the GCMMF, Dr Kurien was awarded the prestigious World Food Prize for the year 1989 - $200,000 annual prize –, which is instituted by the prestigious World Food Programme (WFP). Incidentally the WFP was awarded the coveted Nobel Peace Prize (2020) "for its efforts to combat hunger, for its contribution to bettering conditions for peace in conflict-affected areas and for acting as a driving force in efforts to prevent the use of hunger as a weapon of war and conflict." The WFP, in its citation of the award for Dr Kurien, recognised the contributions of Dr Kurien as “a global dairy distribution leader, who turned the milk shades of India into a cooperative system owned and managed by milk producers who are the producers, processors and market milk for the urban centres of the country”. As a prime mover of the dairy movement in India and so also the architect of “Operation Flood”, the largest dairy development programme in the world, Dr. Verghese Kurien has enabled India to become the largest milk producer in the World. Dr Kurien with an extraordinary vision for benefitting the farmers, particularly the marginalised farmers, devoted a lifetime to realizing his dream – empowering the farmers of India - and befittingly came to be hailed as the “Father of White Revolution”.

Dr Kurien was also befittingly conferred with all the three Padma Awards in recognition of his relentless service to the dairy and farming communities, He was awarded the Padma Shri (1965), Padma Bhushan (1966) and Padma Vibhushan (1999). He also was awarded the Ramon Magsaysay Award (1963), and World Food Prize (1989). He has received innumerable other national and international awards including honorary doctorate from various universities. He is also the recipient of the International Person of the Year Award by the World Dairy Expo in 1993, Ordre duMerite Agricole by the Government of France in 1997, the Regional Award from the Asian Productivity Organization of Japan in 2000, Dr. Kurien has received several honorary Doctorates and Fellowships from leading foreign and Indian Universities / Academic Institutions.

It was therefore no wonder that Dr Kurien’s outstanding achievement and his ability to lead a successful people’s movement and to help the farmers of Anand motivated internationally acclaimed film maker Shyam Benegal to portray the dairy movement and the role of Kurien on the celluloid. Benegal made a film titled ‘Manthan’ which was based on the milk movement in India and the man behind it — Verghese Kurien. Interestingly this film was crowd-funded by 500,000 farmers who donated Rs. 2 each for the making of this film, which is another innovation kind of a sort. Kurien believed that “Innovation cannot be mandated or forced on people,”. He said. “It is everywhere, a function of the quality of the people and the environment. We need to have enough skilled people working in a self-actuating environment to produce innovation.”

Dr Kurien’s services were also used in innumerable other ways by the government including in some non-descript, yet highly pertinent, areas like growing of trees and even to salt farming. His services were also used in the Oilseeds Grower’s Cooperative Project, which was established in 197, to established a direct link between the producers and consumers of oil thus reducing the role of oil traders and oil exchanges. The outcome of this project was to stabilize oil prices, and to provide an incentive to the oilseed grower to raise production and reduce India’s dependence on oil imports. Dr. Kurien revolutionized the edible oil business by introducing ‘Dhara’, which is now a well-known edible oil brand in the market.

Dr Kurien after serving for more than seven decades died from an illness at the age of 90 years on 9th September 2012 at Nadiad Hospital, near Anand. Paying rich tributes on the passing away of the doyen of the dairy cooperative movement in India, the then President, Pranab Mukherjee and the then Prime Minister, Dr. Manmohan Singh publicly acknowledged the extraordinary contributions of Dr Kurien to the rural upliftment and for empowering the people and substantially increasing the agrarian economy.

It is the self-less and untiring efforts and contribution of such great passionate nation builders like Dr Verghese J Kurien and others that has helped India in passing through those early times of trials and tribulations - including having to depend on alms in the form of PL480 for the shipload of wheat to arrive for feeding our hungry population - to the current era where we are not only self-sufficient in feeding our population but India is well set on a path towards becoming a developed nation. On the occasion of the birth centenary of Dr Verghese Kurien, I join all our countrymen in remembering with reverence the contributions of all the founding fathers of our nation, who worked tirelessly in our nation building and we must commit ourselves to continuing their path for seeing a developed India.

On the occasion of the birth centenary of Dr Kurien it is an honour for me to pen this tribute and to join the nation in saluting this great nation builder. May you continue to rest in peace in the heavenly abode which is now home to you Dr Verghese Kurien and may you continue to inspire generation of youngsters and may several of them tread the path which you have shown.